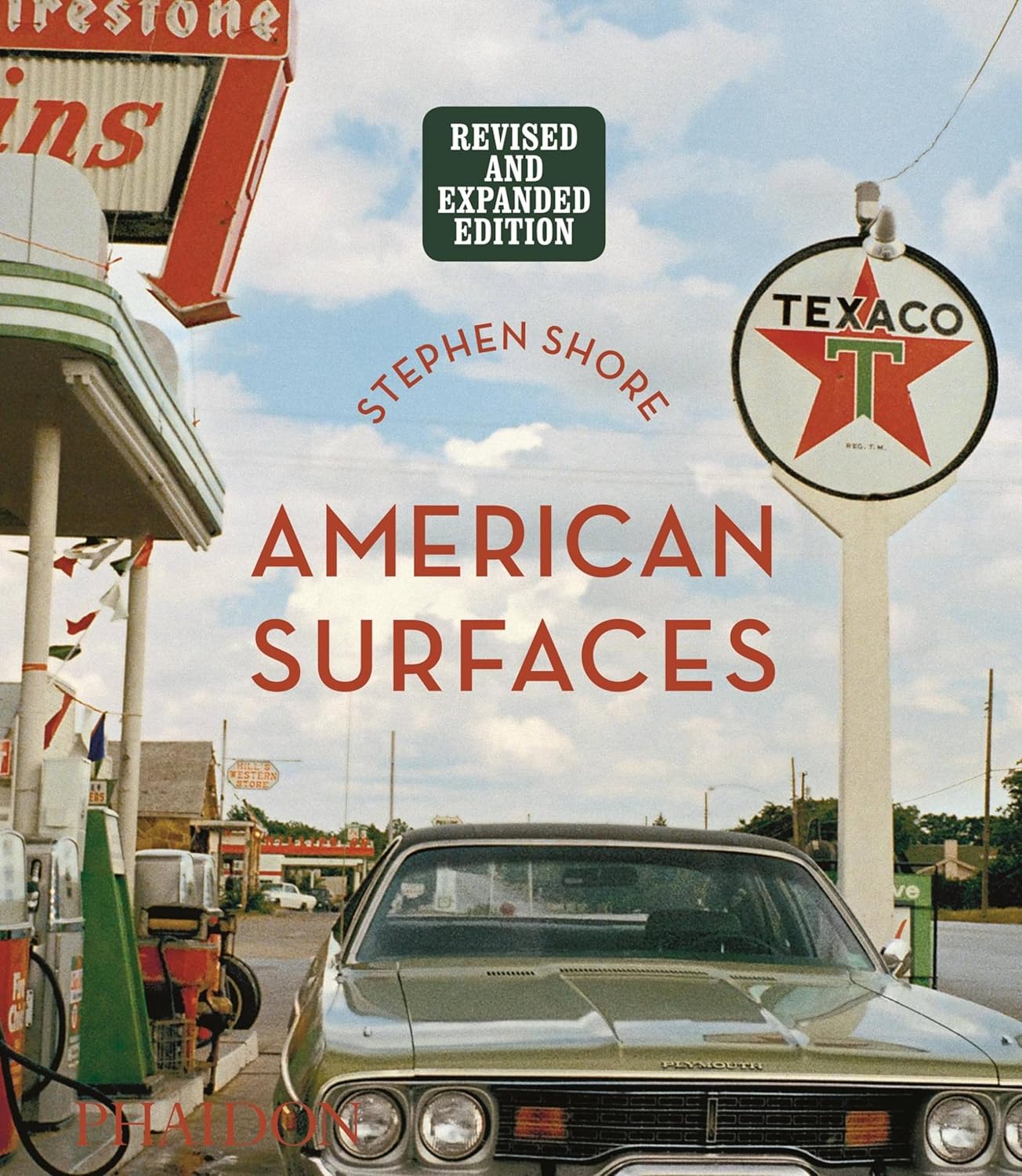

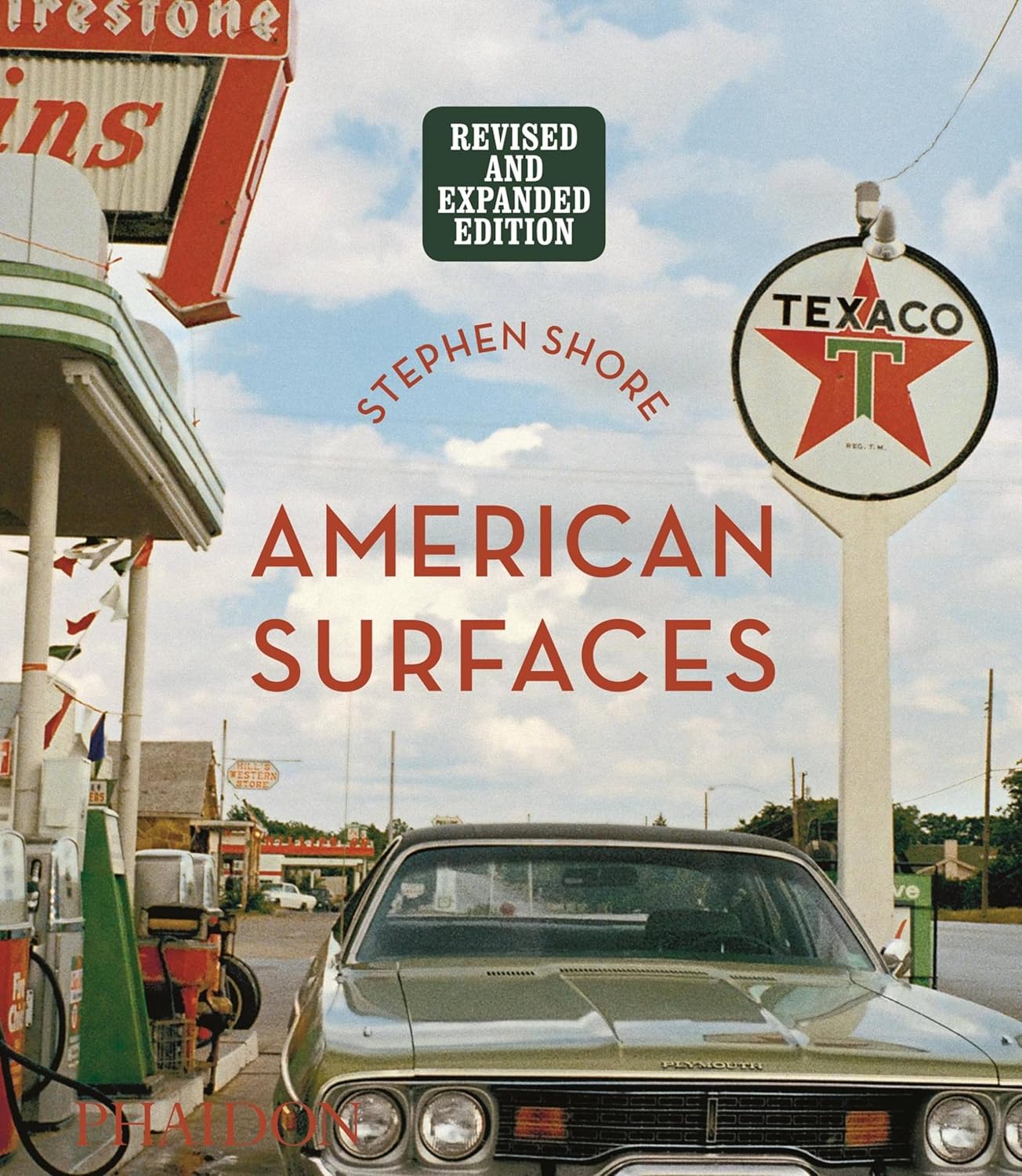

American Surfaces: Revised & Expanded Edition

FREE Shipping

American Surfaces: Revised & Expanded Edition

- Brand: Unbranded

Description

SS: I wasn’t working that closely with the title, but I had that in my mind that this was a general orientation that I was looking at, the surfaces that I encountered, the literal surfaces. What is the external appearance of this world I was entering into? And, so, color played an important role in that. Ginger Shore, Causeway Inn, Tampa, Florida, November 17, 1977 is indicative of the way in which Shore's work in Uncommon Places developed over the course of the 1970s. This image, taken with an 8 x 10 view camera, is from near the chronological and sequenced end of the series. The image is highly saturated and two-thirds of the picture plane is encompassed by a turquoise swimming pool, patterned with light. This photograph is dominated by diagonals; a silver railing in the foreground leads the swimmer into the pool and the viewer into the image, while the edge of the pool cuts diagonally toward the top of the image, separating a receding set of lounge chairs and another body of water. At the centre of the image is a woman, with wet hair, standing in the pool, looking away from the camera, dressed in a royal blue bathing suit. Stephen Shore was born in 1947 and grew up on New York City's Upper East Side. Shore's family was Jewish, and he was the only child. The family owned a succesful business and Stephen lived a privileged existence, with annual trips to Europe and regular exposure to art and other forms of culture. He was given a darkroom set by an uncle when he was six, which he used to develop his family's snapshots, taken with a simple and inexpensive Kodak Brownie, often experimenting with different ways of printing the images using cardboard masks. Shore had little practice taking his own photographs, however, until the age of nine, when his parents bought him a 35 mm camera. Analog photography would seem to demand a more considered approach. If you’re shooting a plate of pancakes with an eight-by-ten, you’re forced to be conspicuous, highly intentional. Or is that wrong? Do you think your early photographs could have been shot digitally? Shore returned from that initial road trip with nearly 100 rolls of film, which he developed as any ordinary person would: He sent them to a Kodak factory in New Jersey. He then showed the snapshots in New York’s LIGHT Gallery in 1972. The art world was not enthused, but Shore continued the project anyway. He kept photographing places around the country (and a few in England) through 1973. This same year, he switched to the large-format camera, first a 4x5 and later an 8x10.

American Surfaces was first published as a book of seventy-two images in 1999. In 2005, consistent with his practice of revisiting and reworking earlier series through the medium of the photobook, Shore published the series in its entirety for the first time, and applied a cohesive structure to the works, grouping them by year and the state in which they were taken (see Shore 2005). These digital prints owned by Tate were made in the same year in an edition of ten. Digital photography allowed Shore to return to reclaim some of the casualness and immediacy of American Surfaces without sacrificing the image quality of Uncommon Places. “Cameras are now made that are the size of a 35 mm SLR that can take a picture that has the resolution of a view camera,” he said. “And so that camera that I was looking for in 1972? By 2008 that camera was being made.” But this is only part of the story. The question remains: why this particular intersection, on this day, in this light, at this moment? That’s more like what you’ve called instinctive. There’s the sense of something taking over. I found on my road trips that, after a couple of days of driving and paying attention to what I was seeing, I would get into a very clear, quiet state of mind. There was a time though that something else changed. When you put an 8×10 camera on a tripod, the decisions a photographer makes become very clear and conscious. There is a period of awareness, of self-consciousness, of decisions […] I felt like I could take a picture that really felt “natural,” or that you were less aware of the mediation, that was harder to achieve when I started using the view camera because of the self-consciousness of the decisions. Over time, I very slowly examined each of the decisions involved in putting a picture together, and played with it, and tried to learn how to do it so that I could eventually get to the point of very consciously taking a picture that had much of the same quality that American Surfaces had, except doing it with this great big camera.”SS: Not necessarily, and when I said I didn’t have a problem editing down, I meant I didn’t feel an obligation to include everything. There’s a lot of work, and the current edition has grown out of looking at some of the pictures that didn’t make it into the previous edition. There were a lot of pictures in the original show in ‘72 that were not included in the previous Phaidon edition of American Surfaces. When The Museum of Modern Art gave me my retrospective in 2017, the curator of the show, Quentin Bajac, wanted to recreate the American Surfaces show. I continued for about half a year photographing for the project after the show went up so Quentin could avail himself of the entire body of work. We decided to expand the original Phaidon book to include those.

Stephan Schmidt-Wulffen was born in 1951 in Witten/ Germany. He works as an art theoretician and director of the art academy Akademie der bildenden KA1/4nste in Vienna/Austria. But the answer to your question could be different at another stage of development. For example, the work I did for “Steel Town,” in the fall of 1977, came at the end of the period of formal exploration I just described. By this time, I really had a handle on formal choices, and I could think about what to photograph and not about how. The content of the pictures was guided by the needs of the commission: to go to cities where mills were closing, and to photograph the mills, the cities, and the steelworkers. I had never dealt with such immediate economic conditions before. And this raised a larger, more central question, something you referred to in your recent review of the Constructivism show at MoMA: does art that springs from political situations have a “use by” date? I understood that a societal event could exist as history, as archetype, as metaphor—or, to use T. S. Eliot’s term, as an “objective correlative.” I hoped to find that point.

In Print

I went to the view camera really for a simple reason that I wanted to continue with American Surfaces, but I wanted a larger negative to make bigger prints, because film at the time wasn’t very sharp,” he said. Look at the first Uncommon Places photos and the continuity with American Surfaces is obvious: For instance, he shoots his hotel television and bed. Soon, however, the images move away from interior spaces toward large images of neglected architecture, parking lots, and street intersections, . He also has been working on a series about Holocaust survivors in Ukraine. It is an unusual project for Shore: Art critics have typically downplayed his photos’ content and discussed instead their formal qualities or conceptual ideas. “I’m self aware enough to know that when I’m doing this, I‘m photographing much more loaded subject matter than I’ve ever dealt with before,” Shore said. “So the question is: Can I take a picture that is not just an illustration of the content but is a visually coherent picture and that could stand alone even if one didn’t know what I was photographing and also somehow communicate some essence of the situation?” I believe Uncommon Places to be about photography showing the beauty of everyday life, while American Surfaces displays the beauty of photography itself by reflecting itself within banal scenes of normality. There is place for both frames of mind, and I actually believe an understanding of the trade-offs between these two reference points is vital for any photographer today.

Shore was born in New York City in 1947, the sole son of Jewish parents who ran a handbag company. At the age of six, he began to develop his family’s photos with a dark-room kit his uncle had given him as a present. He received his first camera a couple years later, and when he was ten he received a copy of Walker Evans’ American Photographs. Shore was a city boy, the only child of prosperous and culture-loving parents on the Upper East Side, and a prodigy, introduced to darkroom technique at the age of six. His mentors included Edward Steichen, who bought prints by him for the Museum of Modern Art when Shore was fourteen. From 1965 to 1967, his nearly daily presence at Andy Warhol’s Factory fostered an aesthetic of seemingly offhand deliberation. Meanwhile, Shore absorbed and gradually transcended formal lessons from the masters of his medium, most notably Walker Evans. He started where others had left off. The compositions became sordid affairs, full of strict attention to detail and precise calibration. The resulting pictures were stark and true, with an emphasis on the hyper-real beauty of interesting scenes in otherwise normal locations. These images are cinematic in nature, bearing uncanny resemblance to even recent films such as The Coen Brothers’ No Country For Old Men. But it is only when contrasted against this later work does Shore’s early American Surfaces begin to make sense from an intentional and artistic perspective. VH: You were born in New York City but your journey took you through small-town America. Were you looking to photograph communities that felt familiar to you or those that felt different from where and how you grew up? The short answer: While I may have questions or intentions that guide what I’m interested in photographing at a particular moment, and even guide exactly where I place my camera, the core decision still comes from recognizing a feeling of deep connection, a psychological or emotional or physical resonance with the picture’s content.It’s an unexpected statement coming from the man who made American Surfaces. But then American Surfaces was not the random result of some photographic compulsion: Shore conceived of and executed it as a disciplined artistic undertaking. “I think there may have been a slight difference,” Shore said about the symmetry between these photos and social-media photography. “When people are posting, I actually find it a little peculiar. Why would they think that I would be curious what they had for breakfast? But this was more a way of using my own experience as—it was about me, but it was also about exploring the culture through this mechanism [the snapshot].” As a teenager, Stephen Shore was interested in film alongside still photography, and in his final year of high school one of his short films, entitled Elevator, was shown at Jonas Mekas' Film-Makers' Cinematheque. There, Shore was introduced to Andy Warhol and took this as an opportunity to ask if he could take photographs at Warhol's studio, the Factory, on 42nd Street. Warhol's answer was vague and Shore was surprised to receive a call a month later, inviting him to photograph filming at a restaurant called L'Aventura. Shore took up this offer and, soon afterward, began to spend a substantial amount of time at the Factory, photographing Warhol and the many others who spent time there. He had, by this point, become disengaged with his high school classes and dropped out of Columbia Grammar in his senior year, allowing him to spend more time at the Factory. The Shorean image is often seen as something that disrupts our idea of America, or of what American imagery can be. But when you first set out on your road trips, in the seventies, shooting the work that would become “American Surfaces,” you hadn’t seen much of the country. How did those trips change your notion of what America was? What surprised you? And was there some value to coming at these places as an outsider? VH: Absolutely! Thank you so much for speaking with me and with Phillips. We’re really excited about the new edition of 'American Surfaces.'

- Fruugo ID: 258392218-563234582

- EAN: 764486781913

-

Sold by: Fruugo